The Financial Times

County Durham not the pits. By Harry Eyres.

Lartington. Barnard Castle. Teesdale

…The party was held in the small market town of Barnard Castle (2 miles from Lartington), where the medieval fortress of Bernard Balliol beetles over the peat-coloured, fast-flowing River Tees. Barnard Castle, at the entrance to Teesdale, one of England’s loveliest valleys, is an entrancingly sleepy and quirky small town, full not just of art galleries and antique shops, but hardware stores and alleyways with greengrocers and florists. The sleepiness is perhaps overdone, with the tourist office closing well before 5pm on a July saturday, but the charm is irresisitible.

Barnard Castle should probably make more of itself touristically, because it is home to one of the finest and most improbable museums in the British Isles. You would not expect to find a large, 19th-century French chateau with a world-class collection of fine and decorative art anywhere in Britain, and especially not in a tiny Durham market town. The Bowes Museum has one of the most romantic stories of any museum, up there with the Victoria and Albert Museum and trumping the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection if not for the quality of the work then for the sheer imaginative largesse of the conception.

John Bowes was the natural son of the 10th Earl of Strathmore who, deprived by lawyers of the earldom but in possession of his father’s Durham estate, set about multiplying his fortune.

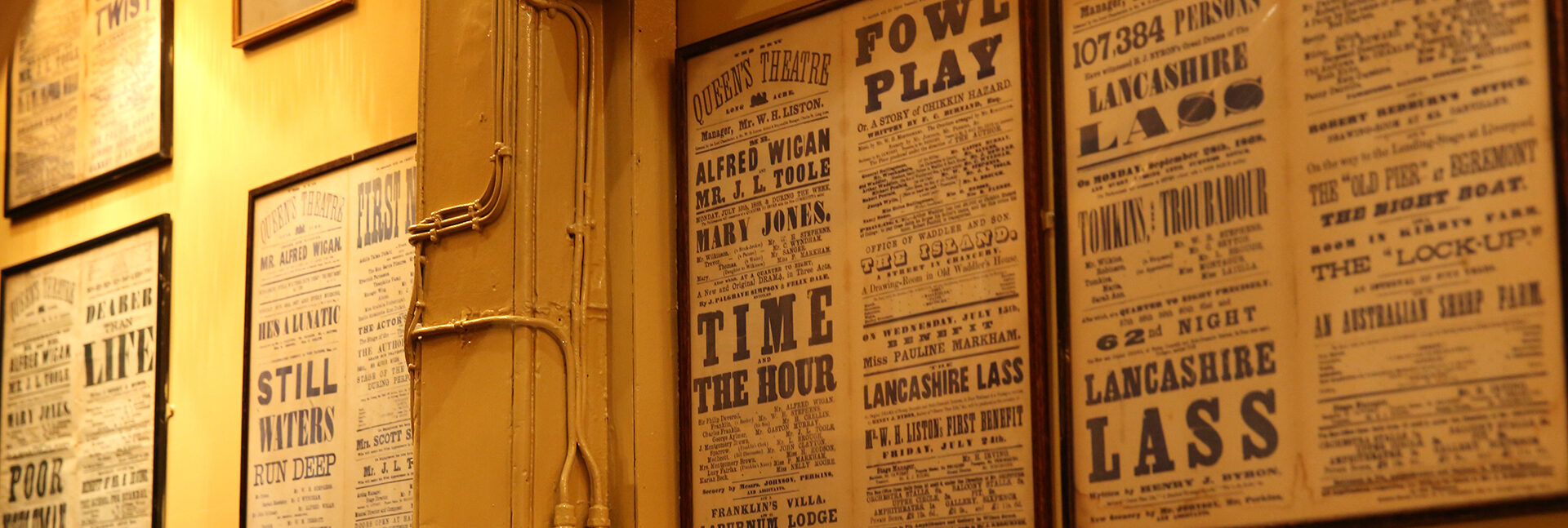

But he was a romantic as well as a shrewd businessman; he not only bought the Theatre des Varietes in Paris but married one of its leading actresses. Then he and his wife Josephine Coffin-Chevallier, a talented amateuar painter, had their brainchild: they would create a museum to make the finest arts of Europe, from Sieneses renaissance altarpieces to French neo-classical porcelain and furniture available to the people of the north-east of England. “I lay the bottom stone,” said Josephine in 1869, “and you, Mr Bowes, will lay the top stone.” Josephine died in 1874, and John followed her in 1885; it would be another seven years before the museum opened, but their immense, generous effort, which saw them purchase 15,000 items between 1862 and 1874, finally had its public consecration. Some 63,000 visitors came in the first year.

The Bowes Museum is big and grand but it is also wonderfully local. The people working there obviously love it (of how many great national galleries can that be said?). And there is no doubt which is their favourite exhibit: the life-sized, solid silver swan, an automaton made in 1765, is a miracle of ingenuity-and as a cheeky note informs you, the world’s only fish-eating swan; it shares a room with half a dozen masterpieces of painting that the locals seem to care less about. There are two huge Canalettos, an El Greco of St Peter, and Antonio de Pereda’s wonderfully tender and graceful painting “Tobias Restoring His Father’s Sight”.

But the work which stayed longest in my mind was Goya’s portrait of his friend Juan Antonio Melendez Valdes, one of the leading figures of the Spanish Enlightenment. In his pale, refined face you see the tragedy of Spain’s flirtation with French Ideals and their terrible consequence.

Melendez Valdes, the leading lyric poet of his age, joined the government of Joseph Bonaparte when the French invaded Spain in 1808. No doubt he was in a difficult position, as was Goya himself, a supporter of the French Revolution and of French Enlightenment ideas. But Goya recoiled when he saw the brutality of the invading troops, and left his searing records of the horrors of war. Melendez Valdez goes down in history as a turncoat who died in dishonour.

So much content in a single small picture, just one of the thousands of works of art which an enlightened and generous couple bequeathed to a particular corner of England.